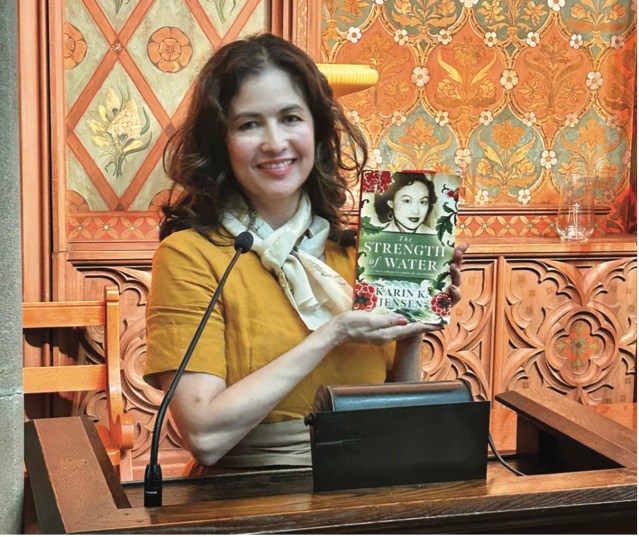

By Neal Wong

A Bay Area author spent more than two decades chronicling her mother’s life journey from war-torn China to working as a domestic servant in San Francisco’s Sunset District, resulting in a book that sheds light on a rarely documented slice of immigrant history.

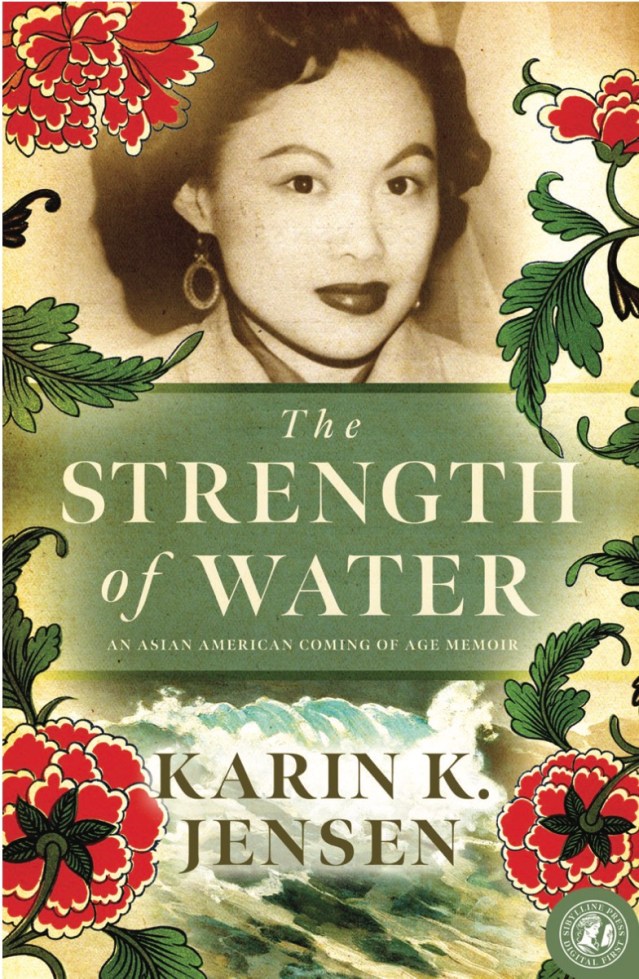

Karin Jensen’s “The Strength of Water: An Asian American Coming of Age Memoir” traces her mother’s experiences from growing up in her father’s Detroit laundry business during the 1920s and ’30s, to surviving the Sino-Japanese War in a rural Chinese village and ultimately working in the home of a wealthy Sunset District family on Ortega Street in the mid-20th century. The book is a first-person narrative.

“This is history from an immigrant daughter’s perspective. This is history from a woman’s perspective,” Jensen said.

The writing process began formally in 2002 when Jensen started recording interviews with her mother, Helen. Jensen said she heard these stories throughout her childhood, but only then decided to take the time to document them. When her husband took a job in New Zealand, Jensen found time to interview other family members.

“I’ve been hearing those stories and thinking that I wanted to set them down,” Jensen said.

Jensen blogged rough draft chapters one at a time while in New Zealand, which her mother read. Her mother questioned the value of the project, wondering who would care about the stories. Jensen spent several years raising children before finishing the manuscript in 2018, five years after her mother passed away.

She took a pause on the work until 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown provided the catalyst for Jensen to polish the manuscript and seek publication. During the extended lockdowns, she worked with a developmental editor and began contacting publishers.

“In that great silence of having so much time at home, I said, ‘This is it, I need to do something with this,’” Jensen said.

The book’s most harrowing sections detail Jensen’s grandmother’s death and the family’s return to China before World War II. Jensen’s grandmother died at 32 after eight pregnancies that included stillborn children and five daughters before she finally bore a son. She chose not to stop having children despite chronic health conditions.

“She felt like that was her duty, to produce the heir to the family,” Jensen said.

With six children and mounting debts from medical bills, Jensen’s grandfather borrowed money from his brother-in-law to take the family back to their ancestral village in China. He found a new stepmother for the children through a matchmaker, then returned to the United States to earn money to eventually bring the family back.

The village lacked the basic amenities the family had grown accustomed to in Detroit. They went from having electricity, a telephone and access to doctors, to living with outhouses, oil lamps and candles. Communication was limited to letters.

“It was stepping back 100 years in progress,” Jensen said.

Then the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. Japanese soldiers were instructed to live off the land, which meant pillaging villages along their path. The family witnessed Zero planes flying so low overhead that they could see the pilots’ heads.

“People make really desperate decisions to survive,” Jensen said. “Are they going to sell a daughter into servitude, so that she can eat and they have one less mouth to feed? Do they commit infanticide? Decisions that we cannot even imagine in our first-world lives.”

When Jensen’s mother Helen returned to the United States at age 16, she was immigrating back in the middle of the war. Her father was sharing a small apartment with other immigrant men and had no room for her, so she stayed with aunts who had their own families.

At 17 years old, Helen went to work as a live-in servant for a family on Ortega Street, set up in the position by an aunt. Helen worked for what she later realized was a family of swingers, though at the time she innocently thought people who fell asleep together after parties were simply drunk.

The book includes details about her being disrespected. While bathing, her employer Alice walked in on her, stared, and casually called to her friend Edith to come look, pointing out that Helen had no body hair. The family also brought their baby and Helen along with them while barhopping.

“When you’re the lowest person on the rung in somebody’s home and you’re kind of looked at as a second-class citizen, people can treat you pretty poorly in the privacy of their homes,” Jensen said.

The social pressures on women across three generations form a central theme of the book. Jensen’s grandmother is characterized as feeling that she had no value without producing a son. Jensen’s mother is depicted marrying a boyfriend without knowing him well, only to discover he had hidden a gambling addiction from her. She felt she could not divorce due to cultural stigma.

“In her culture, to divorce was a disgrace,” Jensen said.

The marriage finally collapsed in 1960 when Jensen’s mother discovered evidence of his infidelity. She faced exactly the isolation she had feared. Chinese friends tried to marry her off immediately, while her American coworkers made snide remarks, treating her with less respect.

Writing about these pressures made Jensen realize how they had influenced her own parenting. When her daughter, who at the time was a student at the University of California, Irvine, mentioned transferring schools, Jensen’s first response was concern about losing a boyfriend rather than discussing academic reasons for the move. She called her daughter back to apologize.

“I always said I was not going to put this pressure that my grandmother felt, that my mother felt, that I felt,” Jensen said.

The book’s title comes from the “Tao Te Ching” by philosopher Lao Tzu. The text says: “Water is fluid, soft, yielding. But water will wear away rock … what is soft is strong.”

“She didn’t wield sword strength, but she persisted forever and a day,” Jensen said of her mother. “She taught me that the hardest landscapes can be transformed through persistence because she really transformed the landscape of her life.”

An overseas publisher first released the book in 2023. After it was selected as a top 100 indie book of 2024 by Kirkus Reviews, Sibylline Press picked it up for republication. The second edition was released in November 2024.

“The Strength of Water” is available from online bookstores and physical copies can be ordered through independent bookstores. Find more information at karinkjensen.blog/the-strength-of-water.

Categories: author