By Kate Quach

Jinyou sprawled herself on the church’s basement floor, picking at the daycare’s fuzzy carpet distracting her little fingers. She did not hear the hushed conversation between the daycare teacher and her mother, Shan Hong, happening a few feet away from her, nor did she see her mother’s eyes widening slowly and her hand lifting to cover the concerned expression worn across her lips.

“I don’t know how to say it, but your daughter’s different,” the teacher spoke in a careful tone. “She’s not like the kids I’ve seen before. I suggest you go to see the doctor.”

Different. The single word gnawed in Hong’s mind. Her faith in the church instructor’s years of teaching experience faltered; Hong could not bring herself to believe that her daughter was different from other children. Still, she kept one eye open. When her eldest son was 1 year old, he could communicate his needs in phrases. Jinyou, then 18 months old, sat fixated in a gaze, completely wordless.

For two more years, Hong’s swelling fear that her daughter possessed verbal dyspraxia, an inability to speak and pronounce words, worsened. Late into the night, angry words clashed between Jinyou’s father and her. The noise of disputing voices crowded the space in Hong’s Sunset District home.

“He never believed that his daughter had autism,” Hong said. “I said, ‘Even though you don’t believe it, we still should get her a therapist or an intervention as early as possible. It won’t hurt if you try and find out that she’s not, but it would hurt so much if you didn’t try but found that she is.’”

Her differences with Jinyou’s father festered. One evening, Hong decided that their relationship had deteriorated beyond repair. When Jinyou received her diagnoses of a speech and language impairment, a severe intellectual disability, and severe autism at 27 months old, Hong provided for her daughter and son as a single mother.

Special day classes begin at 9:30 a.m. every weekday for Jinyou, now 9 years old. Hong bustles through the house, gathering her daughter’s backpack with one hand and her breakfast with the other. She passes by a weekly calendar clinging onto the refrigerator with magnets. Chinese characters fill the scheduler with morning-to-night time slots, reminders, and a list of her children’s sports gear that they would need year-round. Out the door, Jinyou’s bright purple velcro shoes lean on their tiptoes against an outdoor bench before she pulls them on. Standing next to her on the patio, Hong waits for the school bus to settle in a hissing stop at their block.

The teacher starts with a math lesson as, according to Hong, Jinyou must complete the hardest part of the day in the morning.

“Doing math is still such a big challenge for her. She will cry,” Hong said.

The tears have lessened, but Jinyou still relies on counting her fingers for addition and subtraction.

After music class, recess and group activities, she steps off the bus at 4:15 p.m. On some occasions, Hong takes Jinyou to watch her brother race from each end of the pool during his swim meet. Yet, for most afternoons, Jinyou attends her Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) speech therapy sessions in the lower floor of her home. Jinyou’s vocal expression has been limited to short-worded requests, such as “apple,” “strawberry,” or “sleep with mommy.” She stuffs her hands in the pockets of her vest, struggling to describe the emotions written on her face, like the smiling freedom of “happy” or the stubborn cries of “angry.” Hong observes that responding to greetings and resisting the urge to repeat the speaker troubles her daughter. Still, says the mother, Jinyou’s vocals are growing, which is more comforting than nothing at all.

In the times when Jinyou cannot speak, she draws instead. She hugs a thick sketchbook with a black cover before letting it escape her arms and tumble on the table. Her hands peek out from their hiding spot in her pockets to point at the vibrant illustrations filling the once white paper with full color. A rainbow stretches across one page while a star-adorned unicorn — a character matching the ones on her slippers — leaps over the scene. Hong looks over Jinyou’s shoulder and asks her daughter to name each drawing aloud: Cupcakes, chickens, bird monsters, hamburgers. Jinyou eagerly flips through the pages and lets her fingers trace the bright pictures.

“A lot of her drawings are in her imagination and are more colorful than her words,” Hong says lovingly.

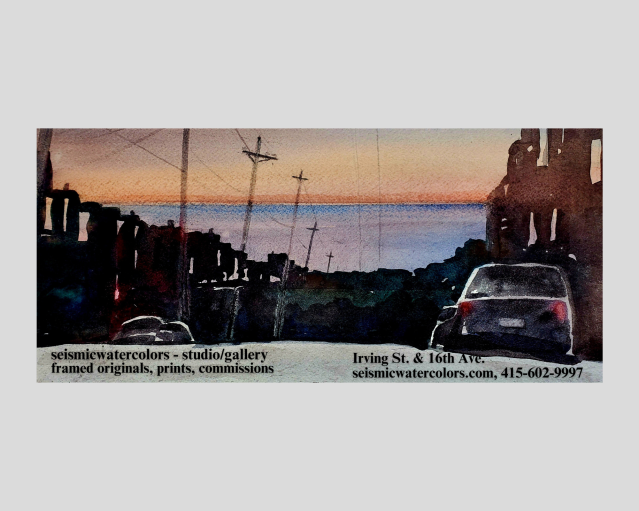

The window beside Jinyou’s sketching corner spills the orange cast of a sunset. Then, the dark sky sinks deeper into the evening. Jinyou, unfazed by the night, happily continues coloring, though Hong rubs her weary eyes underneath her glasses and yawns from the day’s compounding exhaustion. After navigating the schedule between home, her son’s sports competitions, after-school programs and her job, she aches for rest. Yet Jinyou’s eyes continue to glow brightly with energy.

“She has a severe sleeping disorder that means she’s very energetic 24 hours a day,” Hong said. “It’s very hard for her to fall asleep. It’s going to take one or two hours, even though we follow the daily routine.”

In the pale mornings, the mother holds her head in her hands, trying to wake herself up so she does not enter a constant mental state of daydreaming. She must be alert for her children, who both require attention and resources for their ADHD and learning disabilities.

Hong’s mother lives with them, but she cannot speak English nor understand the labels wrapped around Jinyou’s bottles of medication. The single provider of the household sighs deeply. She reaches for her own prescription pills stashed in a drawer to settle the clamor of ADHD and anxiety fidgeting throughout her body.

“I feel really helpless,” she says softly.

Some days, parenthood with special needs children delights her with reward. In other instances, she regrets having kids. Arguments with Jinyou’s father and the possibility of sacrificing one child’s activities over the other drained Hong emotionally. Her body clung to her bed after sending her children to school. She thought about her son, whom she left when he was 2 years old and reunited with in the United States when he was 8. The other half of Hong became embodied in Jinyou, who was the only child that she raised independently in America.

Hong understands that she and her mother are getting older. Besides her children and their grandmother, she has no extended family in the United States.

“I love Jinyou so much,” she said, “but I worry so much. I always think that if one day I die, who’s going to take over this job of taking care of her?”

Since her separation with Jinyou’s father, Hong sits down in weekly sessions with her therapist, who advises her to take frequent breaks. If she is not working at her part-time job as a Mandarin and English interpreter, Hong spends every other moment with her children.

Sunshine splashes overhead one afternoon at Torpedo Wharf. Her son, unable to contain his enthusiasm to catch crabs, bounds with excitement toward the long strip of pier sticking out into the water. Hong, whose hand clasps Jinyou’s, walks while enjoying the view. Gulls squawk while fishermen toe the edge of the thin ledge, casting their fishing line into the green seawater lurching underneath the pier. Hong’s son squats on the weathered wooden planks and fixes some bait into the crab trap. Playful sea lions nudge their noses above the water.

Hong laughs and reaches for Jinyou’s elbow so that she would look over. But her hand passes through empty air. Panic seizes Hong. Her head flicks from side to side, searching for her daughter. Jinyou’s foot dangles at the skinny rim of the pier, a step away from the plunge off deck and into cold water. Without thinking, the mother grabs her daughter into her arms. Gasps, horrified yet thankful, overwhelm Hong.

The memory has carved itself in her mind.

“I’m scared, my heart breaks. It’s like she wanted to jump in,” she said.

A shiver ripples through Hong when she reads statistics about the causes of death in children with autism, a high percentage of which is drowning. According to the Autism Society of Florida, children with autism are “160 times more likely to drown than their neurotypical peers” and “nearly all gravitate toward water.”

Hong does not hesitate to decide that Jinyou must learn how to swim.

“If something happens, like if she slips into a river, she can at least know how to get her head up and try to save herself,” Hong said. “Secondly, she will know how dangerous the deep water is.” Hong pays extra for Jinyou to take lessons. To swim becomes a form of protection, one that lasts when Hong’s arms are not nearby.

On Tuesday evenings, Hong drives Jinyou to the Sava Pool located in the Sunset District. She watches as her daughter gains confidence in treading water. Seeing Jinyou enjoy her childhood stirs emotions of Hong’s childhood. Hour-long swimming classes become routine on Friday afternoons at the Janet Pomeroy Recreation and Rehabilitation Center. With her coach, Jinyou ventures to the deep end, learning when to hold her breath and coordinate her arms and legs to stay above water. At home, a clothesline strings from rung to rung on the patio deck. Hong slings the pool towels over the line to dry. In the breeze, they flap like a family of banners.

The mother and daughter have become each other’s life raft. In uncharted waters, they keep each other afloat, side by side. Time slips through Hong’s fingers as Jinyou and her son are no longer little babies but growing children. She says that she holds pride for her children and their special needs. Hong’s affection for her children compels her to attend classes at City College to study child development and special needs advocacy. She wants to help other parents know that they are not alone.

She reminds herself, “If you cannot change it, just live with it. Take care of yourself. Only after taking care of yourself are you in good condition to take care of your kids.” She adds one last reminder to her list: “The kids are growing faster. Spend more time with them.”

Different. The word no longer rots isolated in Hong’s mind. Instead, it blooms in a garden alongside “family” and “love.” Hong and Jinyou hold each other dearly. Their hands fit together perfectly, like rhymed words in Jinyou’s palm. She tugs her mom close to her side.

“I know that Jinyou will be accompanying me for a long time,” Hong says. “We are bonding with each other, and she will be there for me and I will be there for her.”

Categories: Health