By Woody LaBounty

Several months ago, we got through Golden Gate Park’s concert season, and the grassy meadows and fields were in recovery mode from the stages, tents, beer stalls and tens of thousands of tromping, dancing feet of the Outside Lands and Hardly Strictly Bluegrass festivals.

How many of those music lovers wondered if polo had ever really been played on the Polo Fields, what the heck its strange eight-sided tower was for and why wasn’t someone selling some decent pour-over coffee out of it?

I can answer the first two questions. You’ll have to ask the Recreation and Park Department about the coffee question. Seems like a good idea to me.

The Sporting Set

We fight over whether people should be able to drive in Golden Gate Park or whether it should be turned over to slower, more human-powered activities. It is not a new issue.

The first fine paths and lanes created in the 1870s attracted speeding carriages, buggies, phaetons, surreys and the annoying Tesla drivers of the day: Young men who wanted to show off and race each other on horseback. These guys would totally gallop past you in the restricted bus lane today.

Another not-new issue: People with money can usually get what they want in Golden Gate Park.

In the late 1880s, a group of wealthy sporting men tired of being chided for running over be-bustled women and petticoated children convinced the Park Commission to create a straight, flat “speed track” just for their racing.

They did this using one of the oldest tricks in the book, one that still works today. If the City created it as a benefit to “the people,” they, the rich guys, promised to pay for its upkeep, improvements, etc.

As usual, the commissioners fell for it.

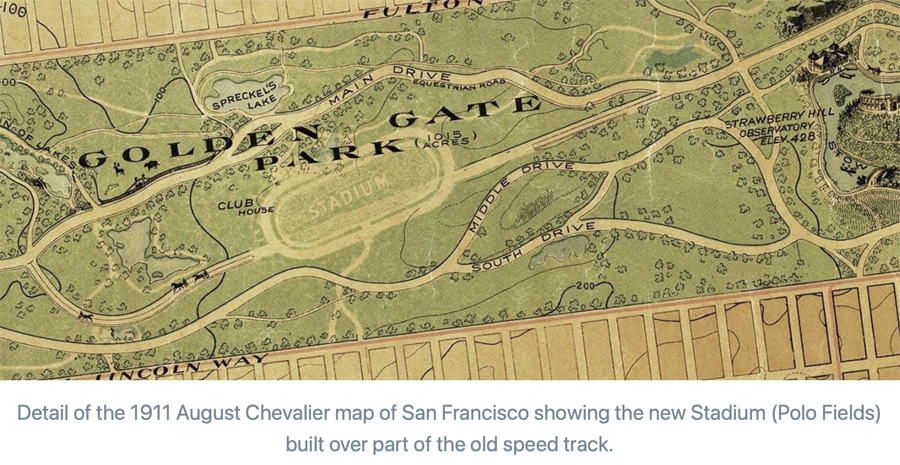

The speed track ran roughly from Rainbow Falls at today’s John F. Kennedy Drive straight southwest through Speedway Meadow (now officially Hellman Hollow, but let’s pretend that awkward rechristening never happened, shall we?) and on along what is now the southern boundary of the Polo Fields through “little” Speedway Meadow on the west and ending just past where the Bercut Equitation circle is today.

Must have been fun, and it is a great origin story for the name Speedway Meadow.

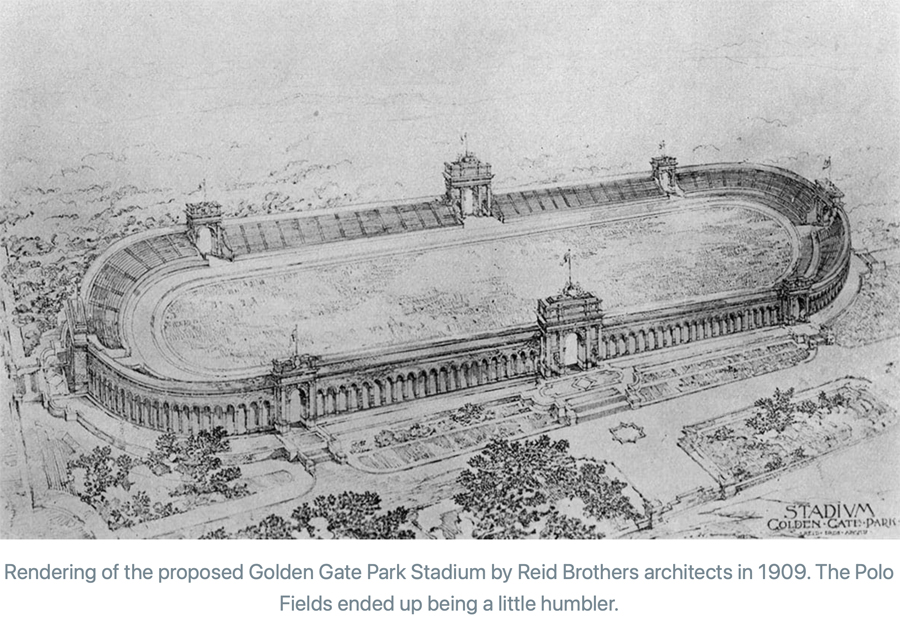

The rich guys and the park commission could never agree upon a satisfactory maintenance plan and soon all were on to another great idea. How about an American version of the Roman Coliseum in the park?

The Stadium

The idea of lions eating Christians probably wasn’t floated during Park Commission meetings, but chariot races might have been. Because as much fun as racing in a straight line on horseback was, the real sport for lovers of the track in the 19th century was harness racing.

You know, guys with whips perched on little gigs going around in circles. It was the NASCAR stock car circuit of the time.

Because it was a shocking disgrace that a world-class city like San Francisco didn’t have a proper track in its public park, rich men pushed for the creation of one and even pledged, even pinky promised, to raise the money for a stadium if the City would just get it started.

Yep, the Park Commission fell for it again. At least this time it did get some money from the racers, using $20,000 from the Amateur Driving Association to help create what we today know as the Polo Fields. The big dedication ceremony was held three months after the 1906 earthquake and fire.

The hobbies of the wealthy also included another equine activity – polo. You and I might play at being well-to-do by golfing, but wheat is separated from chaff when you start talking about investing in polo ponies.

Polo had been played on Golden Gate Park’s Big Rec field in the 1890s. By 1904, the plutocrat set began constructing dedicated polo fields in San Mateo and Burlingame.

Rudolph Spreckels became seriously bitten by the polo bug, and since his brother, Adolph B. Spreckels, was the chair of San Francisco’s Park Commission, polo was promised to be a major use of the new stadium. And, of course, the polo-ists promised to kick in funding.

The harness racers could speed around the mile oval and the polo ponies could romp in the bowl, and all the rich horse owners would be benefactors of the big project. That was the general idea.

In 1907, the City received a donation to build an octagonal judge’s stand for the finish line of the harness race track, a perch to make decisions on close finishes.

The Amateur Driving Club kicked in money to build the first section of concrete bleachers across from the judge’s stand in April 1909, the big start to the Reid Brothers architects’ 150,000-seat California version of the Colosseum.

But that was it for the Colosseum plan. For most of my lifetime that hulk of seats, stranded a mile away from any action on the grassy bowl of the polo fields, was a mysterious piece of random detritus apparently dropped there by alien visitors.

The concrete bleachers proved handy in 1911 for the ground-breaking ceremony of the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition, when President William Howard Taft turned a spade of earth beside the judge’s stand. In the end, however, almost all the fair’s activities were in today’s Marina District, where a whole new temporary stadium and track were constructed.

Finishing or improving a project just doesn’t attract the big bucks, then or now.

Anyway, that’s where the tower came from, part of a plan to host horse races that didn’t quite take off because rich people have short attention spans and new diversions came on the scene.

Polo Anyone?

Polo players, it turned out, didn’t want to bring their ponies up to San Francisco and kept their games on fine club fields on the peninsula.

Harness racing had a heyday at the new stadium, but died away as raising and racing horses gave way to tinkering with and driving gas-powered machines.

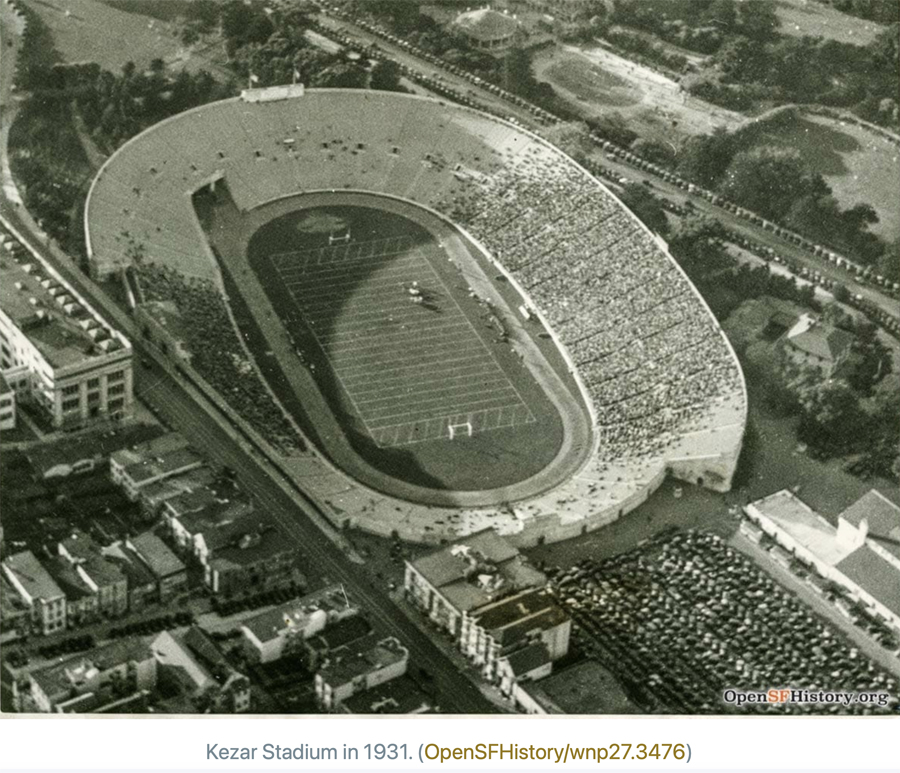

By the 1920s, Colosseum dreams shifted to a new popular sport called football. It was called a shocking disgrace that a world-class city like San Francisco didn’t have a proper modern venue for the sport (here we go again), and rather than adapt the 15-year-old oval along the old Speed Track, a whole new project, Kezar Stadium, was erected on the old park nursery near Stanyan and Haight streets.

Polo finally came back to the park in 1922, when the local subcommittee of the American Polo Association wanted to make the sport more “accessible” and arranged a few matches at the old stadium.

Once Kezar was constructed and the park nominally had two stadiums, the name “Polo Fields” became commonly used for the older field in the western half of Golden Gate Park.

The local polo folks were instrumental in getting the bowl’s wooden bleachers installed. Matches were played off and on there through the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, along with bicycle races, soccer, marching bands, model airplane tournaments, rugby matches, prayer rallies, and later rock concerts.

I believe it has been about 60 years since a polo pony trotted on the turf.

Historian Woody LaBounty was born and lives in the Richmond District and has spent most of his life on San Francisco’s west side. LaBounty and a friend started the Western Neighborhoods Project (WNP). After he retired from his position as WNP’s executive director, he moved over to San Francisco Heritage where he is the president and CEO.

This story and photos with captions were reprinted with permission by LaBounty. To read more and sign up for his weekly newsletters, go to sanfranciscostory.com.

Categories: San Francisco

Thank you for this informative article about the history of the Polo Field.

The grassy Polo Field has been used for soccer and other sports in recent years. The grass is not only environmentally beneficial (grass sequesters carbon like crazy), but also helps the area blend into Golden Gate Park’s parkland when the birds and other wildlife populate it.

A few years back, the grass avoided being paved over with artificial turf, probably because plastic grass does not stand up to trampling by the concert-goers who come for Outside Lands, etc. Unfortunately, the concerts have not saved the grass completely. The Recreation and Park Department decided to pave the western end of the Polo Field with a swath of ugly concrete for the concerts that happen only a few times a year (so far). And thus the commercialization of our parks to generate income continues.

We will see this happen with the Upper Great Highway. Voters may have voted for YES ON K thinking they will be able enjoy nature at her best – free of human impact – but the opposite is going to happen. RPD is already planning to bring in commercial events and built elements. For our Recreation and Park Department, nature is never enough.

LikeLike