By Noma Faingold

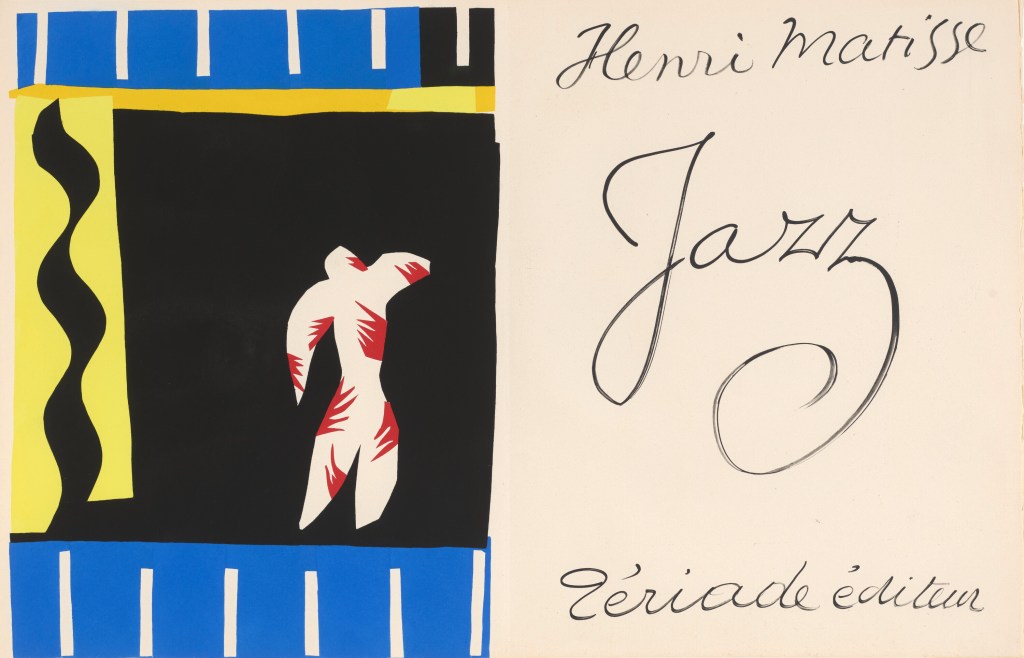

Originally, the very limited edition of artist Henri Matisse’s 1947 book of prints was going to be called, “Circus,” because the inspiration for several motifs concerned performing artists and balancing acts. However, during the two-year period of creating 20 color stencil prints (pochoirs), the title changed to “Jazz,” at the suggestion of Greek art publisher Tériade.

Matisse (1869–1954) embraced the new title because he saw the connection between visual art and musical improvisation.

“These images, with their lively and violent tones, derive from crystallizations of memories of circuses, folktales and voyages,” Matisse explained in the hand-written accompanying text.

In early 2024, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco acquired a rare, pristine unbound copy of “Jazz” and will be showing off the then-radically illustrated book in an exhibition called “Matisse Jazz Unbound,” at the de Young Museum from Jan. 25 through July 6.

“The acquisition is a really big deal. It’s a luxury book,” FAMSF Curator of Prints and Drawings Natalia Lauricella said. “It was a top priority. ‘Jazz’ is considered the pinnacle of Matisse’s graphic art.”

The exhibit consists of the 20 unbound, framed works, which Lauricella refers to as “plates,” lining the walls of a main-floor gallery, along with four other bound Matisse books from the museum’s collection, to be displayed in vitrines.

When Matisse began the project in 1943 at age 74, he was not well. He underwent risky surgery in 1941 after being diagnosed with abdominal cancer. Post-surgery, he was grateful to be alive, but he was confined to his bed and a wheelchair until his death at 84. In spite of his physical limitations and the German occupation of France (where he lived), he produced some of the most vibrant and dynamic works of his career.

He no longer had the mobility to paint or sculpt. However, Matisse reinvented himself by turning to “drawing with scissors,” which he had secretly experimented with in the past. The cut-out technique was innovative – his invention. It was the first time cut-outs were used as a medium, rather than as a tool. His assistants helped prepare the paper in vibrant colors using gouache (opaque watercolor paint) and he cut it into simple shapes that would be arranged as decoupage and collages to his liking.

While working on “Jazz,” Matisse was often in pain and was plagued with various ailments, including liver problems, deteriorating vision and insomnia. The silver lining of his chronic insomnia greatly informed the composition of “Jazz.” Working with artificial light at night led to nighttime scenes, including figures surrounded by deep blue-sky hues.

The imagery of “Jazz” combines whimsical with themes of horror. The viewer can interpret each plate in different ways. Matisse was apolitical while living in Southern France during the war. But there are references to figures of that time, such as in the piece, “The Wolf.”

“He had family members in the resistance. He felt anxiety and despair,” Lauricella said. “The symbolism of ‘The Wolf’ is the Nazi Gestapo. ‘The Wolf’ has a menacing head and a purple background.”

“The Nightmare of the White Elephant,” with its jagged red slashes that pierce the elephant balancing precariously on a small ball, may reflect how isolated Matisse felt trapped in his physical confinement and in his life as a driven, anxious artist. In the “Jazz” text, he writes, “An artist must never be a prisoner. Prisoner? An artist should never be a prisoner of himself, prisoner of style, prisoner of reputation, prisoner of success, etc.”

Lauricella’s goals in mounting the “Matisse Jazz Unbound” exhibit is “to show how inventive he was and interested in printing and in making artist books,” she said. “He was a true multimedia artist.”

In the second paragraph of “Jazz,” Matisse made his intentions clear in the oversized cursive text.

“All that I really have to recount are observations and notes made during the course of my life as a painter,” he wrote. “I ask those who will have the patience to read these notes the indulgence usually granted to the writings of painters.”

“Matisse Jazz Unbound” will be exhibited Jan. 25-July 6, at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive. Learn more at famsf.org.

Categories: Art