By Noma Faingold

Cakes, pies and candy.

One of California’s most famous visual artists, Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021), is so much more than his iconic (and unironic) paintings of comforting confections. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) is about to prove that with a complex exhibition called, “Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art,” opening March 22 at the Legion of Honor.

The show could be viewed as a retrospective, but not in the traditional sense. It includes the nostalgic Americana subject matter he painted throughout his career, which began in the 1940s, as well as his off-kilter San Francisco cityscapes (starting in the 1970s), his colorful patchwork delta landscapes inspired by agricultural surroundings near his Sacramento home and his stark portraits/figurative works. The not-so-happy clown series, which he painted toward the end of his life, is also represented.

The most unique elements of the exhibit include 30 copies he painted of masterworks (from Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn to Édouard Manet), most of which have never been seen by the public.

In addition, the museum is showcasing Thiebaud’s own impressive art collection of works by contemporaries, like abstract expressionists Richard Diebenkorn and Willam de Kooning, whom he admired, as well as by those who came before him. He preferred to have the work of other artists than his own on the walls of his modest Sacramento and Potrero Hill homes.

“Wayne was so knowledgeable about art history and this show reveals that clearly,” said Timothy Anglin Burgard, curator of “Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art.” Burgard spent a year and a half conceptualizing, investigating and preparing the exhibition.

“He would have enjoyed this. His message about the history of art being available and open to everyone as a communal, collective continuum is so present in his work in the exhibition,” Burgard said.

According to Burgard, the Ednah Root Curator in Charge of American Art for the FAMSF, Thiebaud taught art and art history for 60 years, 30 at the University of California, Davis. Often, he semi-facetiously referred to himself as a “thief” and a “plagiarist.”

“Other art was a source of inspiration,” Burgard said. “He appropriated that source of inspiration. But he reinterpreted it and transformed it. He had fun with it.”

Thiebaud’s stepson Matt Bult, an accomplished artist and the chairman of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation in Sacramento, was eager to lend a significant amount of Thiebaud’s art to FAMSF because he believes “Art Comes from Art” advances his stepfather’s legacy.

“A show like this is long overdue. He appropriated other artists to problem solve and learn from their styles,” Bult said. “He was very interested in teaching and all its forms, and this is a teachable exhibit. There’s a lot there.”

Bult, 69, was three years old when his mother, Betty Jean Carr, married Thiebaud. He remembers Thiebaud as “an absentee father” in Bult’s pre-adolescent years, while Thiebaud worked in his studio 12 to 14 hours a day and was not to be disturbed. Once older, Bult and his younger half-brother, Paul, played tennis with Thiebaud, who was an avid player into his late 90s.

As a young adult, Bult started handling administrative work for his stepfather at his studio and learned a lot about his creative process.

“I was privy to all his painting practices,” Bult said. “I saw how he developed a painting from the ground up and that had an influence on me.”

When Thiebaud wasn’t working or teaching, he could be found on the tennis court. Occasionally, in the middle of a workday, Bult would get a call from his stepfather.

“He would say, ‘This is your CEO, and you need to get here because we need a fourth.’ So, I would change clothes and go,” Bult said.

Thiebaud was born in Mesa, Arizona to Mormon parents. A year later, the family moved to Long Beach, California. He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from Sacramento State College (now California State University, Sacramento).

Before Thiebaud gained acclaim as an artist, he took a leave of absence from teaching in 1956-57 and made a pilgrimage to New York to meet his artist heroes. Among them was de Kooning and they became friends. He showed de Kooning his work and asked his opinion. According to Burgard, de Kooning was blunt. He didn’t see anything that distinguished Thiebaud from other artists of the era.

“He told him to find something he loved and that’s what he should paint,” Burgar said

Upon returning to Northern California, he pursued simple shapes like triangles, circles and squares. It just so happened that Thiebaud was drawn to the ordinary, but quintessentially American food and how it was displayed, such as baked goods in glass-enclosed cases, pie slices one might find at a roadside diner and cheeses at the deli counter with tubes of salami dangling from above. Thiebaud thought that pinball, gumball and slot machines said a lot about what Americans wanted, consumed and valued. He wasn’t judging because the paintings were so inviting, pretty and almost tactile.

“Painting cereal boxes and slices of pie on plates was revolutionary,” said Scott A. Shields, chief curator and associate director at Crocker Art Museum. “He was doing things in our world that everyone relates to. He made us see ourselves perfectly. Some of these things don’t really exist anymore, so it’s a bit melancholy.”

The Sacramento museum considered Thiebaud a hometown hero and has staged solo shows of the artist’s work in every decade since the 1950s, including the posthumous, “Wayne Thiebaud: A Celebration,” in the spring of 2022.

Thiebaud’s breakthrough came in 1962 at a well-received solo show at the Allen Stone Gallery in New York City. All of his paintings were sold.

Thiebaud was erroneously grouped with the pop art movement of that time. On the one hand, his 1950s-early ’60s paintings of hot dogs and lollipops slightly predate the Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” phenomenon. On the other hand, Thiebaud realized he benefitted from the pop art explosion.

“He took offense to being lumped in with pop artists. He saw it as impersonal and machine made (as in silk screening images),” Burgard said. “What bothered him the most is that his work is beautiful and luscious. He loved that he could transform oil paint into frosting.”

Thiebaud went on to great success. His works are in permanent collections at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art and de Young Museum, among other institutions. In 2020, his 1962 painting, “Four Pinball Machines,” sold for a personal auction record of more than $19 million.

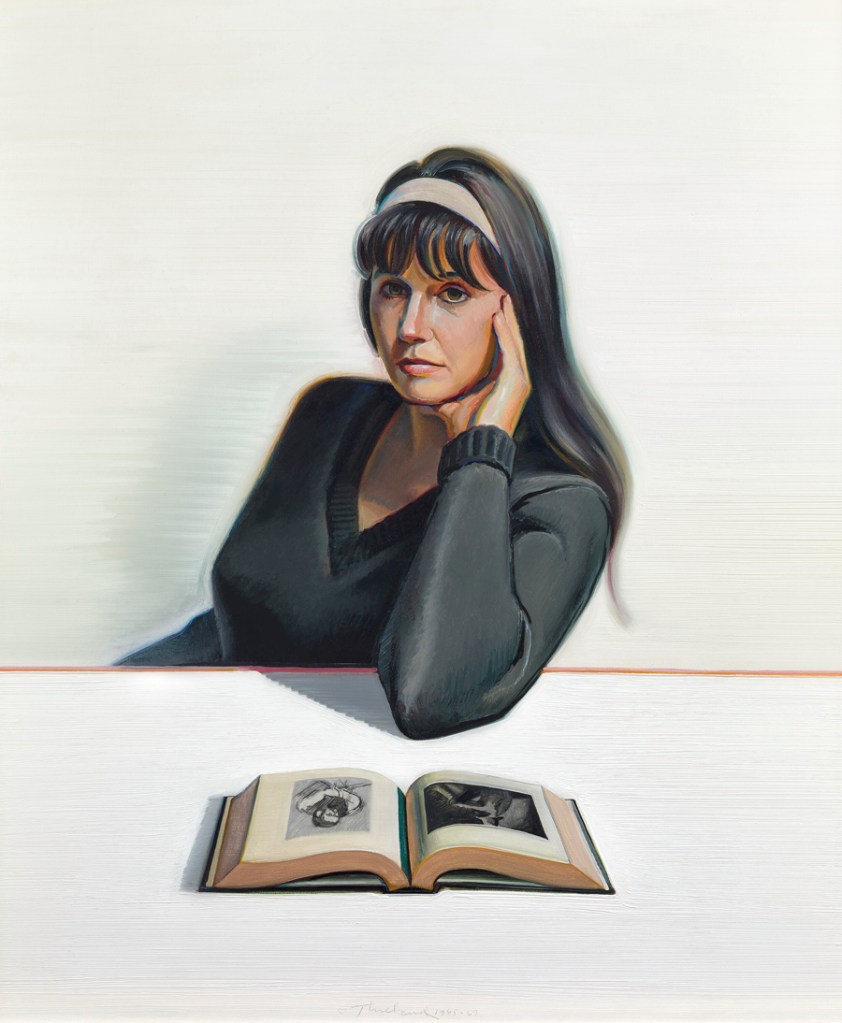

The first painting that guests will see when entering the “Art Comes from Art” exhibition is a portrait of Thiebaud’s wife titled, “Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book” (1965-69). She is seated, one elbow resting on a table and her hand touching the side of her face. There is an open art history book in front of her. He has said that he approached painting a portrait the same way he tackled a still life.

“His wife and art history – his favorite muses,” Burgard said. “It’s a tribute to his favorite model, who he said was also his best critic.”

“Wayne Thiebaud: Art Comes from Art” will be on view at the Legion of Honor, 100 34th Ave., March 22-Aug. 17. Associated events: A Talk on Wayne Thiebaud, March 22, 1 p.m. and Wayne Thiebaud Cake Picnic (outdoors), March 29, 10 a.m.-1 p.m. Learn more at famsf.org.

Categories: Art