By Noma Faingold

Calling someone an “icon” is often an overused sentiment. However, when it comes to the late multi-hyphenate Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1919-2021), the moniker is appropriate, especially in San Francisco, where he thrived artistically and socially since his arrival in 1951.

With all of his accomplishments, perhaps he is least known as a visual artist. That might change when an exhibition titled “Ferlinghetti for San Francisco” opens at the Legion of Honor on July 19.

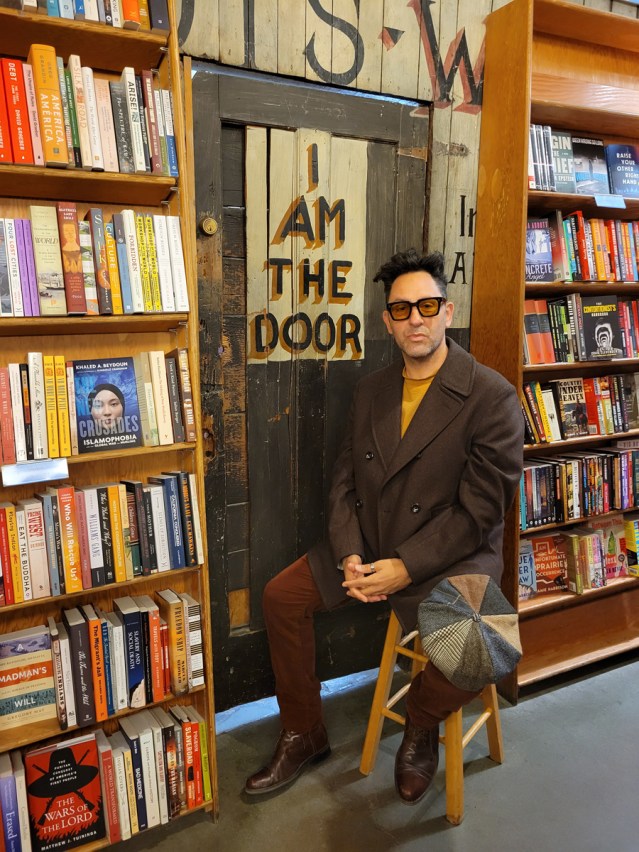

“This exhibition is so much needed. It’s a little bellwether awakening from the sleep that we are all in,” said Mauro Aprile Zanetti, a writer and filmmaker, who was Ferlinghetti’s assistant and collaborator from 2013 until he passed. “This exhibit is a seed. We need a full retrospective. Lawrence was like the fog of the City. He was one of those pillars in all that he represented and what he allowed to happen. It’s the time to unearth these jewels.”

Zanetti consulted with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) to help the exhibit of more than 20 drawings and prints take shape. Natalia Lauricella, curator of Print and Drawings at Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts for FAMSF, utilized the institution’s permanent collection, bolstered by gifts from local artist Sue Kulby in 2017 and the Lawrence Ferlinghetti Artworks Trust in 2022.

“The exhibition honors a San Francisco bohemian and his inclusive, creative spirit,” Lauricella said. “It will remind us of the City’s radical artistic past.”

San Francisco’s first poet laureate – awarded in 1998 – had been making art since he was 10 years old, sketching long before he was writing. He always had a sketchbook with him, no matter where he traveled. The Legion exhibit will display a small sketchbook from when he spent time drawing during a visit to the museum in 2002.

Ferlinghetti has described his early years as Dickensian. His Italian immigrant father died months before Ferlinghetti was born in Bronxville, New York. When he was an infant, his mother was committed to a mental hospital. He was raised by an aunt in Paris until age 5 when she returned him to New York to stay with other family members. Any hope of a stable homelife ended with the 1929 stock market crash. He wound up in a New York suburb, where he was taken in by another family who sent him to a boarding school.

In 1941, he earned an undergraduate degree in journalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He then served in the Navy during World War II for four years, including as captain of a submarine on D-Day (invasion of Normandy). He was then transferred to the fight happening in the Pacific. Upon seeing what the atomic bomb did to Nagasaki, he became a pacifist.

He returned to college after his naval service, getting an advanced degree in English Literature at Columbia University. Taking advantage of the G.I. Bill, he earned a doctoral degree at the Paris-Sorbonne University in 1950. He met his wife Sheldon Kirby-Smith (Kirby) in 1946 on a ship headed to France. Turns out, she was on her way to the same school in Paris.

They left Paris at the end of 1950 and arrived in San Francisco on Jan. 1, 1951.

Why San Francisco?

“It seemed like it was the last frontier,” Ferlinghetti said. “It seemed like you could do anything you wanted to here.”

In 1953, he co-founded City Lights Bookstore (initially called City Lights Pocket Book Shop) in North Beach with Peter D. Martin. The idea was to make the 300-square-foot space the first paperback-only bookstore in the country, with the intention of democratizing culture.

Paul Yamazaki, 76, who has worked at City Lights for 55 years, and as a buyer since 1981, watched the shop and publishing house gradually expand.

“He brought in a group of people who shared the vision, and he trusted us to do our jobs,” he said.

There were stools and chairs, encouraging patrons to linger. To this day, it is a gathering place to share ideas, find progressive, thought-provoking works of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. The bookshop is an independent operation in its truest form. In its infancy, it was Martin’s idea to keep the store open until midnight.

“They were attracting different kinds of people, like the Beats,” Zanetti said. “He didn’t consider himself a Beat poet. But he got into that stream.”

An important milestone was when Ferlinghetti published the incendiary “Howl” by Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. In 1956, Ferlinghetti was arrested for selling “lewd and indecent” material. He went to court with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) defending him. They won a landmark ruling in favor of free speech in 1957. The case established legal precedent.

“Publishing and defending ‘Howl’ is foundational to City Lights,” executive director and publisher at City Lights Elaine Katzenberger said. She began working at the bookstore in 1987, before moving into the publishing wing as an editor in 1993. “He was risking his business. That steadfast commitment to the defense of free expression is part of the DNA of City Lights.”

Ferlinghetti’s most read poetry collection is “Coney Island of the Mind” (1958), which has sold more than one million copies. It has been described as a tome for resistance and a wake-up call for past generations – as well as the current generation – to what many in the community saw as the nightmare of the military industrial complex in the United States.

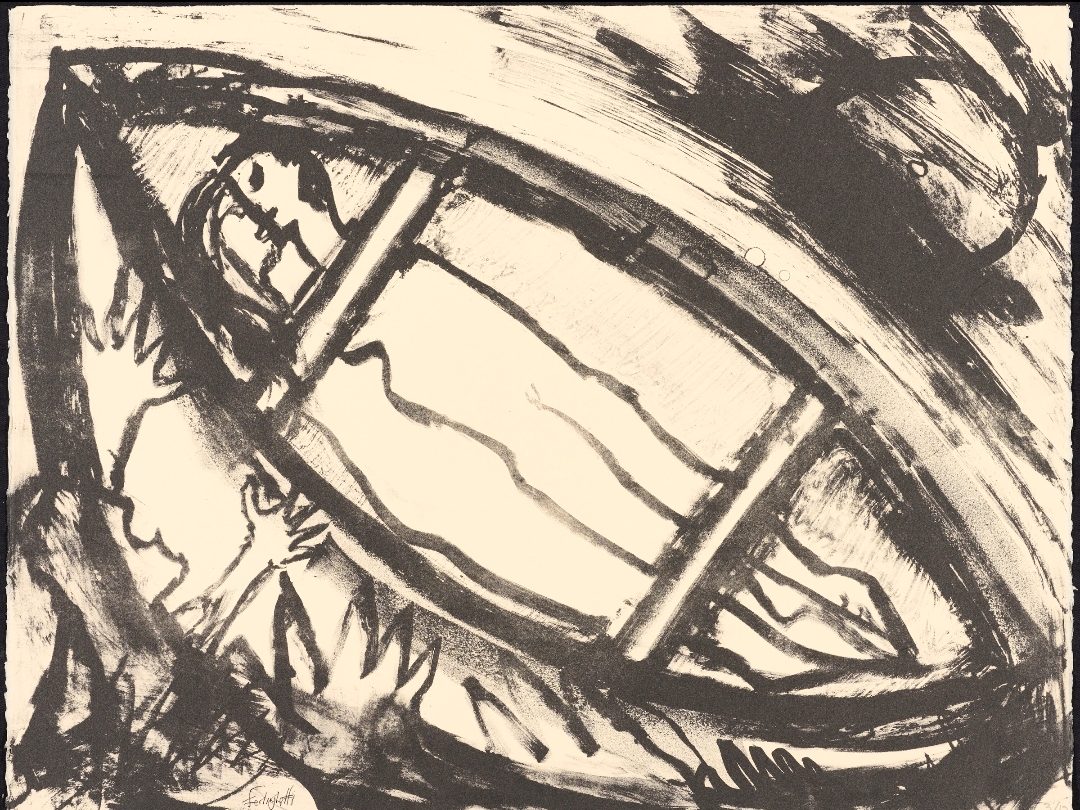

Critics have said Ferlinghetti’s poetry has a visual dimension. He explored parallel themes in his writing and visual art. In fact, many of his paintings contain words, phrases and slogans. He added them spontaneously while creating imagery.

“I never wanted to be a poet. It chose me. I didn’t choose it,” Ferlinghetti said. “One becomes a poet almost against one’s will, certainly against one’s better judgment. I wanted to be a painter, but from the age of 10, these damn poems kept coming. Perhaps one of these days they will leave me alone and I can get back to painting.”

“The way he wrote is exactly like in his sketches,” Zanetti said. “He was so simple. It was just a stream. The words came from the street. They were words of a daily life. The simplicity is so powerful, it knocks you down. Words are wounds on the canvas in his paintings.”

For 40 years, Ferlinghetti painted at his Hunters Point Shipyards studio. According to Katzenberger, he went to the studio almost every day.

“Painting was central to him, not what he became or who he considered himself to be,” Katzenberger said. “Maybe he was a little disappointed for that part of his life, which didn’t take off. He had gallery exhibitions before. I’m sure he’d be very happy about this museum show.”

Ferlinghetti, who was influenced by artists J.M.W. Turner and Francisco Goya, had a bold and unfussy painting style that focused on political and literary themes. He also painted female nudes, and images of boats and the sea.

“His art feels unfiltered. There’s a lot of free expression and it’s a little avant-garde. You get a sense of the hand,” Lauricella said. “Painting gave him some freedom from social and intellectual expectations in his public life. He could create without editing. The human condition comes through in his poetry and his art. The exhibition will show another side of him.”

When Ferlinghetti was losing his sight due to glaucoma around 2016, he could not easily paint or sketch anymore. With Zanetti’s assistance, he continued to work on his final novel, “Little Boy.”

“I was his eyes,” Zanetti said. “The book was already drafted. We were just cleaning up a few things. We edited it together and finished it.”

The somewhat autobiographical book was released on March 24, 2019, on Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday. Zanetti noticed a sharp physical decline in Ferlinghetti after the novel was published.

“He was quite fragile,” he said. “He was done. He was always quoting Samuel Beckett.”

There are still reminders of Ferlinghetti throughout the shop, such as signs he painted on the walls that read, “Stash Your Cell Phone” and “Be Here Now.”

“Some human beings are extra special,” Katzenberger said. “He knew what he was here to do, and he did it. He was beloved and respected. I am glad I knew him and got to be part of something really beautiful.”

The “Ferlinghetti for San Francisco” exhibition opens July 19 and runs through March 22, 2026, at the Legion of Honor Museum, 100 34th Ave. To see exclusive Ferlinghetti content from the exhibit, visit famsf.org/stories/changing-light-lawrence-ferlinghetti. Mauro Zanetti’s writing about Ferlinghetti can be found at famsf.org/stories/living-poetry-lawrence-ferlinghetti-san-francisco. For more information, visit famsf.org.

Categories: Art

1 reply »